This essay was written as a student project for HIST 7250: Practicum on the Place-Based Museum at Northeastern University in Fall 2024.

Looking at the manicured landscape of Boston Common today, it is easy to forget that this land was once inhabited by the varying nations of Indigenous peoples who made the Shawmut Peninsula their home long before Europeans knew it existed. Outside of their inclusion on the Founder’s Memorial as witnesses to the arrival of Europeans, these first inhabitants who resided on the Common are entirely absent from the official historical narration of this place. Through years of public works projects, and later deliberate archaeological excavations, the remnants of these Indigenous communities have been uncovered---and while much remains unknown, their history is just as important as that of the people memorialized all around the city.

Inhabiting the Common

The region surrounding present-day Boston was inhabited by Indigenous peoples as far back as 12,000 years ago. Thinking more locally of Boston Common in particular, there were three nations which historians believe may have made use of this land: the Massachusett, the Naumkeag, and the Pawtucket (Native Land Digital). The lifeways of these nations would have altered greatly across the 10,000 years they lived here before European arrival. As such, the indigenous habitation is divided into three periods:

- The PaleoIndian Period (12,000 – 9,000 years ago) during which people lived as nomadic hunter-gatherers.

- The Archaic period (9,000 – 2,700 years ago) when people began to build temporary housing structures at seasonal camps.

- The Woodland period (2,700 – 400 years ago) a time when the climate had stabilized enough for people to build larger villages and inhabit a single place for longer periods of time. (The Atlas of Boston History).

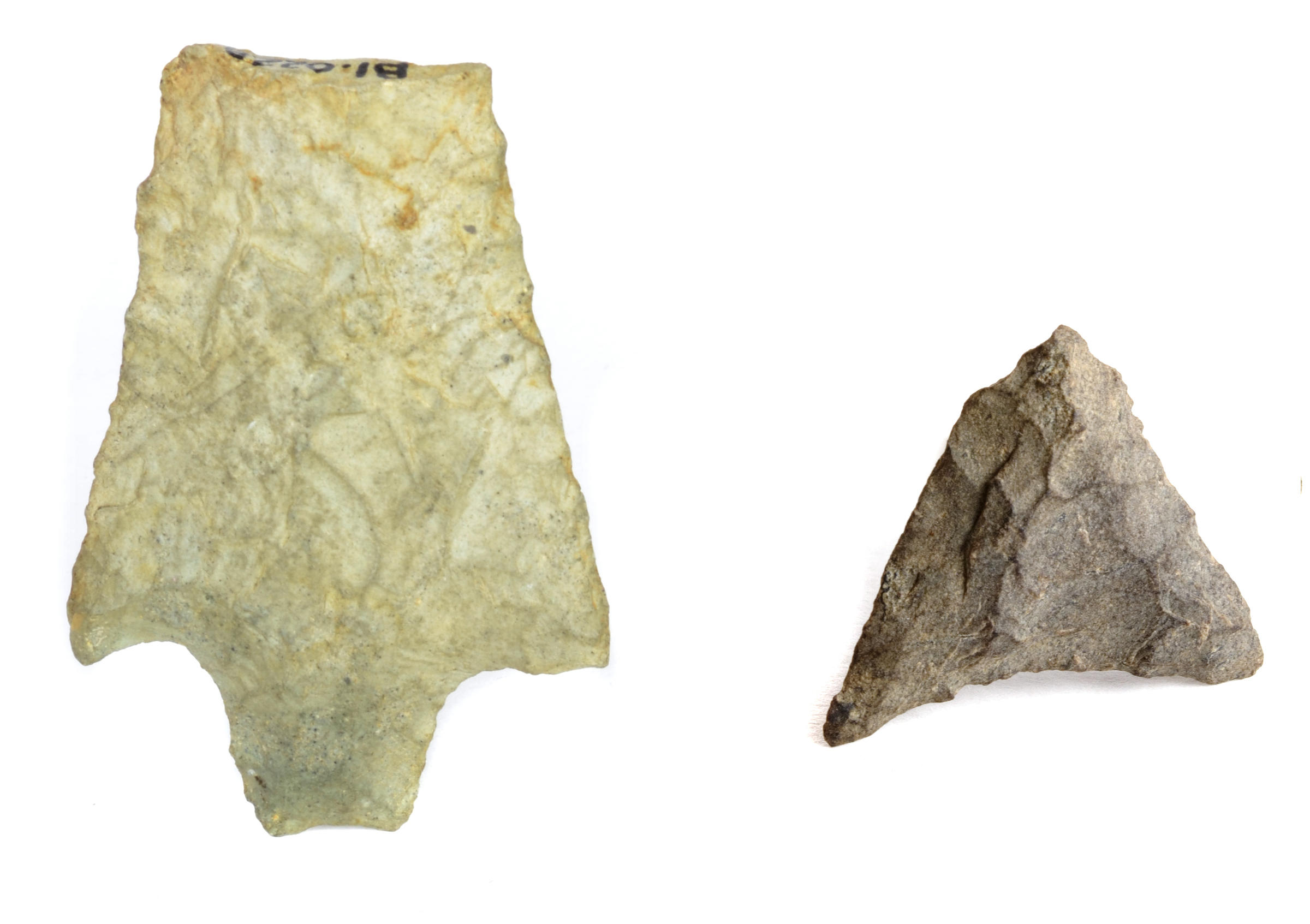

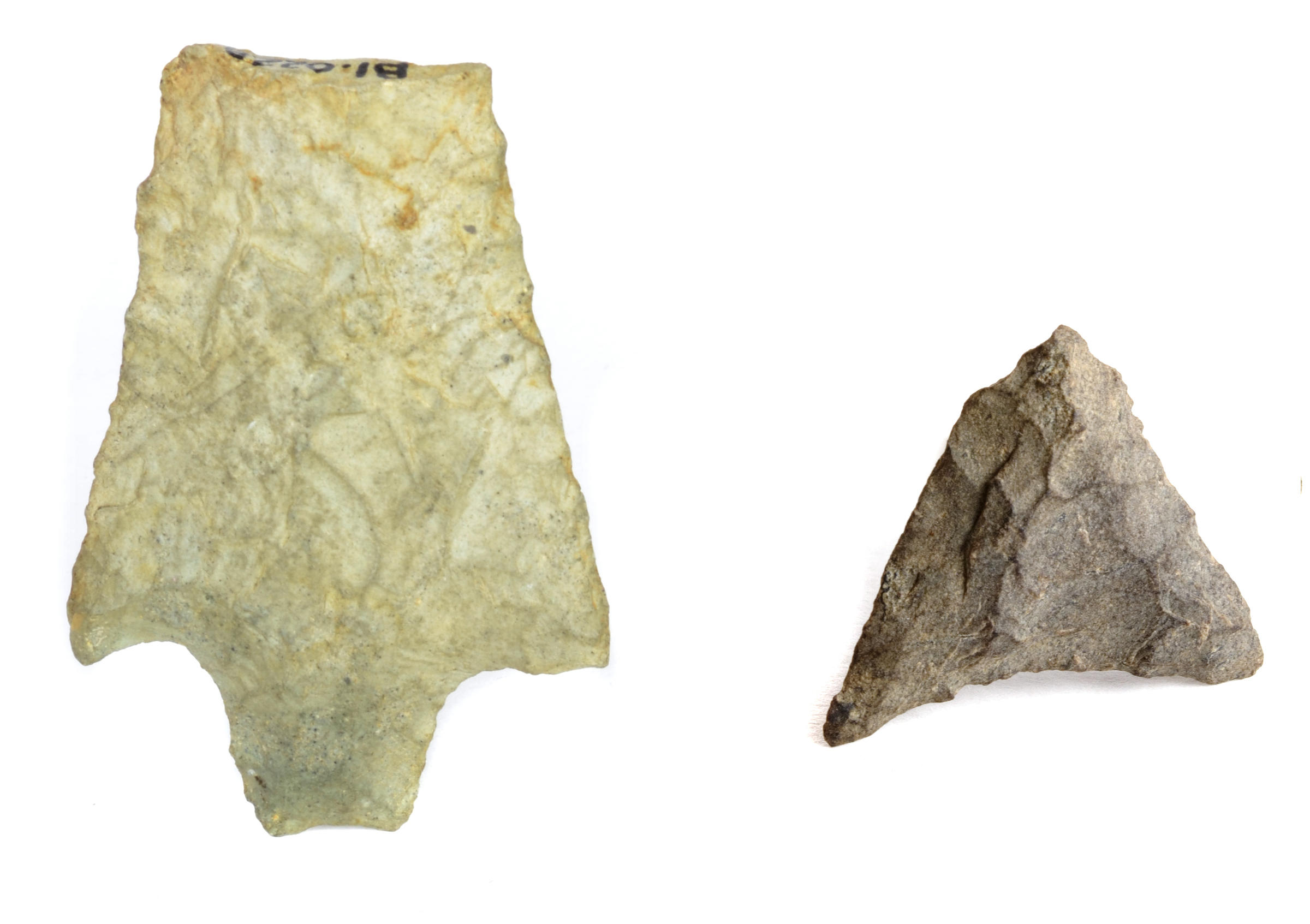

It is from these final two periods that these two artifacts date:

Stone tools found by the City of Boston Archaeology Department.

Stone tools found by the City of Boston Archaeology Department.

The object on the left is a fractured spear point dating to the Archaic Period. On the right is a complete arrow point from the Woodland Period. These two projectile points were unearthed near Frog Pond on the Boston Common during an excavation by the Boston Archaeology Program from 1986-1988. Under the direction of Steven Pendery, the city archaeology team, along with over 100 volunteers, excavated 150 test pits around the Common in advance of the installation of new light posts (Probing Boston Common) and found several indicators of Indigenous land use. In addition to the projectile points above, the excavation uncovered fragments of pottery and thousands of clam shells. The finds showcased the numerous layers of habitation that occurred on the Common before European settlers arrived, but they are hardly the only such discoveries relating to the history of the Common.

The Boylston Street Fish weir

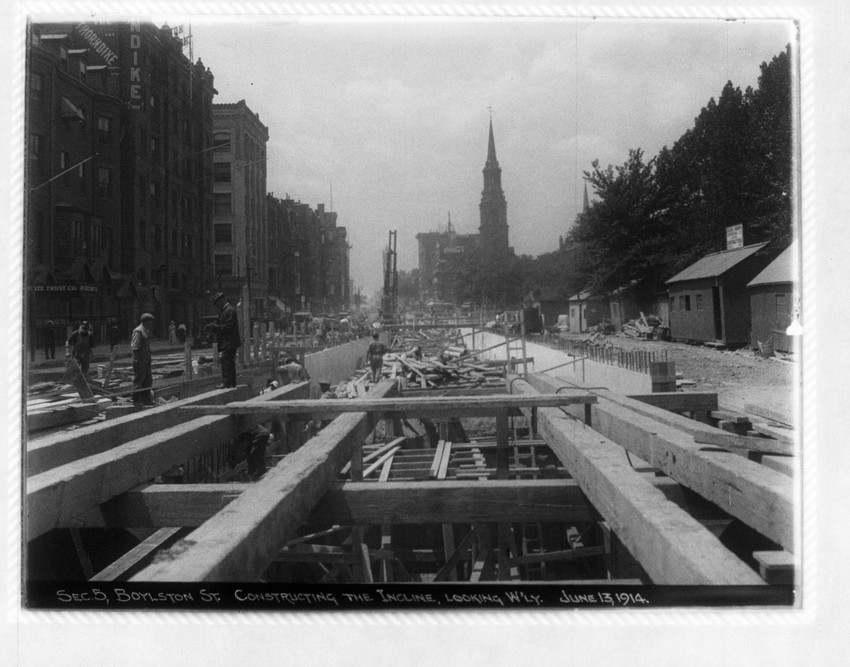

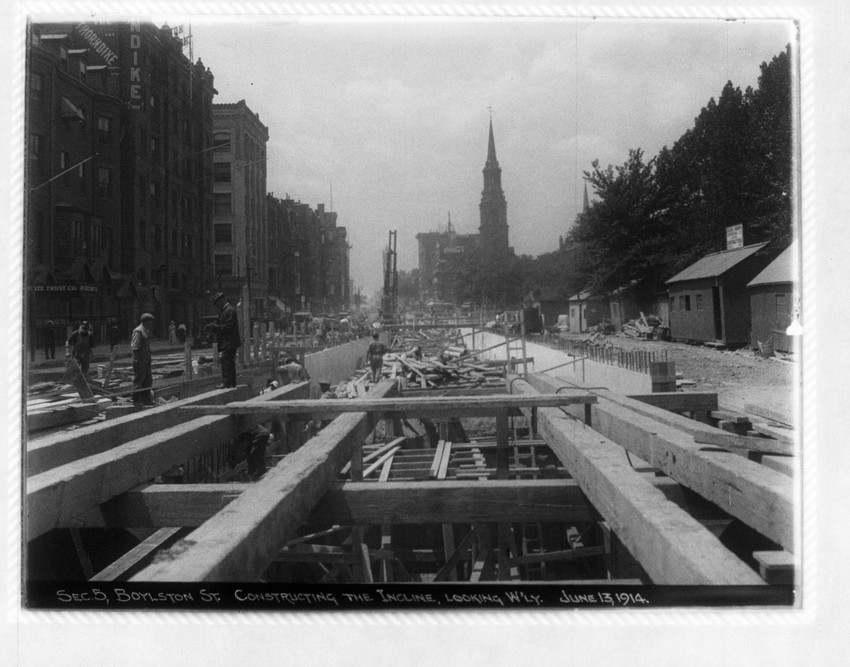

While the City Archaeology Program has uncovered numerous pieces of evidence since its creation in 1983, large scale construction work to develop the Back Bay and build the subway system led to the collection of numerous artifacts 70 years before. Perhaps one of the most exciting finds occurred in 1913 during the excavation of Boylston Street for subway construction, seen below.

Construction on Boylston Street subway line (Historic New England)

As the construction crews dug up the land that had been used to fill in the bay less than 100 years before, they found remnants of Massachusett people’s presence.

The workmen discovered a number of decayed, upright stakes, interlaced with horizontal “wattling” buried deep in the silt beneath Boylston Street. —Fredrick Johnson (The Boylston Street Fishweir)

What had been uncovered were fragments of ancient fish weirs. A fish weir is a structure that is constructed in the water and works similarly to a large-scale basket to trap fish when the high tide recedes. After the fish were trapped indigenous peoples would collect the them and then take them to an area, in this case the Common, to be dried and stored (Boston Uncovered: Joseph Bagley).

Fish weir stake found in 1939, Boston City Archaeology*

Since the 1913 archaeological finds, evidence of fishweirs has been found in the Back Bay during construction projects in 1939, 1946, 1957, and 1986. At each stage the samples have been carbon dated, presenting a case for periodic reconstruction and use of the fish-weirs for a period of 1,500 years (The Boston Back Bay Fish Weirs).

Sharing Hidden History

With most of the evidence of indigenous peoples on the Common still buried in the ground, it is important to think of how this history can be shared. Since 2002 the (Ancient Fishweir Project), under the direction of artist Ross Miller, has reconstructed a fishweir on the Common near Charles Street (Fig. 4) as part of “Making History on the Common,” a free event for Boston schools.

Fishweir Dedication Ceremony, Ancient Fishweir Project

Overseen by members of The Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag, and joined by the Wampanoag Nation Singers and Dancers, this events helps increase awareness and education surrounding the history of the indigenous peoples of Greater Boston. While the fishweir may be built by children, it serves as a reminder to visitors of all ages that the Common had a history before Boston.

Stone tools found by the City of Boston Archaeology Department.

Stone tools found by the City of Boston Archaeology Department.