This essay was written as a student project for HIST 7250: Practicum on the Place-Based Museum at Northeastern University in Fall 2024.

The Custom House

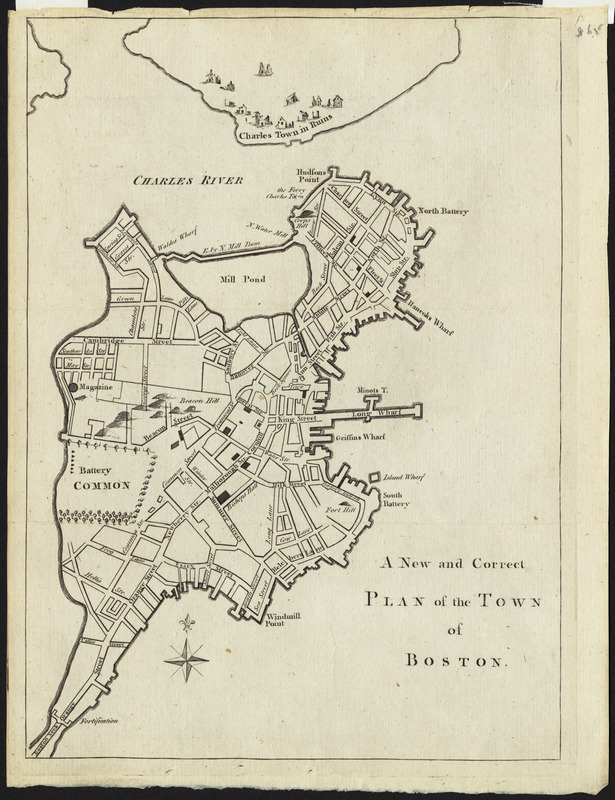

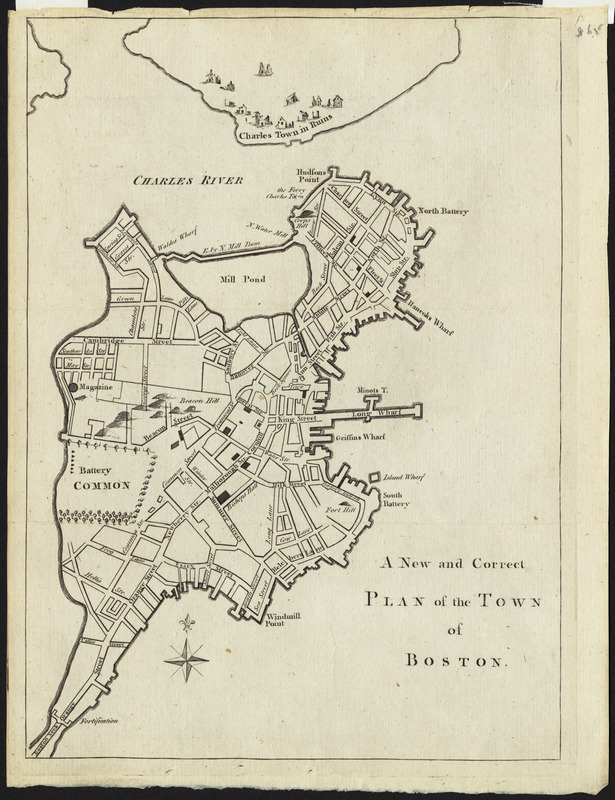

Today the Custom House is located on McKinley Square off of State Street, near the waterfront. There have been a few locations of the Custom House; beginning in 1674 it was located at Richmond Street and Ann Street, in 1770 the Custom House then moved onto State Street near the Old State House until 1805, and in 1810 the customs officials moved into a building between Broad Street and India Street. Despite the changing locations of the Custom House, customs officials had presented their power over Boston economics and maritime trade, especially during the moments leading to the American Revolution.

Trade Under the British

To earn more profits off of the revenue of maritime trade in North America, the British passed a series of laws to raise more money from the colonies for the debt the British monarchy had accrued from the Seven Years’ War. The Custom House and its officials were the enforcing power of British laws and their attempts at economic control in the American colonies.

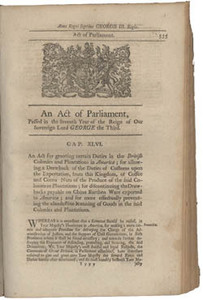

In 1764, the Parliament passed the Sugar Act that raised taxes on foreign goods including molasses, refined sugar, wine, coffee, and textiles. The Sugar Act also prohibited the importation of foreign rum. The Sugar Act also noted the roles of customs officials as enforcers of this new set of taxes and shipping restrictions, ensuring that every ship was carrying the correct and legally documented goods. The law was supposed to help facilitate trade between Britain and its colonies in America.

The Stamp Act was passed a year later in 1765. The Stamp Act required American colonists to pay a tax on official documents, newspapers, and playing cards. Stamps issued by Britain were attached to documents to show that the tax had been paid. The Stamp Act increased the cost of legal transactions, like the buying and selling of land, the signing of indentures, and obtaining liquor licenses. The Stamp Act received a lot of resistance from the colonies, resulting in a boycott of imported British goods. That boycott led to the repeal of the law a year later.

The Townshend Revenue Acts were passed in Parliament in 1767. These laws were meant to help pay for the expenses of governing the colonies by placing duties on imports of glass, lead, paper, and tea. The Townshend Acts also made the customs process more strict, adding more customs officials, the implementation of search warrants and writs of assistance, and the creation of a Board of Customs Commissioners based in Boston. Like the Stamp Act, the Townshend Acts met much resistance from American colonists and resulted in increased hostility toward the British.

Smuggling as an Economic Necessity

Smuggling was commonplace in colonial ports and harbors. Some smuggling involved European imported goods, but most smuggling runs were connected to trade with the West Indies. An article in the June 17, 1765 edition of the Boston Evening Post defended the smuggling of West Indies goods like molasses, stating that the cause of the smuggling trade was, “the difference in prices of the produce of the English West Indies islands and those of the French and other nations.” Smuggling was crucial to the economic survival of Boston merchants after the passing of the Sugar, Stamp, and Townshend Acts. As Brian Deming writes in Boston and the Dawn of American Independence, “Smuggling was rampant, yet over thirty months [the British customs officials] had netted only six seizures, and of those only one was successfully prosecuted.” Although custom officials were given new reign of authority over the economy of the harbor, smuggling practices still persisted.

Rising Revolutionary Tensions

As smuggling persisted along the Boston waterfront, customs officials were still trying to exercise their power over merchants and their cargo. Violence and riots against customs officials were growing. A riot ensued after the seizure of John Hancock’s sloop, the Liberty. Customs collector Joseph Harrison, along with his eighteen-year-old son, and customs comptroller Benjamin Hallowell, went to Hancock’s Wharf to seize the Liberty in the name of the Crown. As they were leaving the wharf, a mob of those who witnessed the ship’s seizure pursued them. Joseph Harrison wrote on June 17, 1768, in a letter to Lord Rockingham, “We had scare got to the street before we were pursued by the Mob which by this time had increased to a great Multitude. The onset was begun by throwing Dirt at me, which was presently succeeded by Volleys of Stones, Brickbatts, Sticks or anything that came to hand.” This instance led the American Board of Customs Commissioners to flee to Castle William under the safety of the Governor. Such displays of violence and revolt against British officials would prompt the arrival of British troops in Boston.

Towards Beacon Hill

Towards Beacon Hill